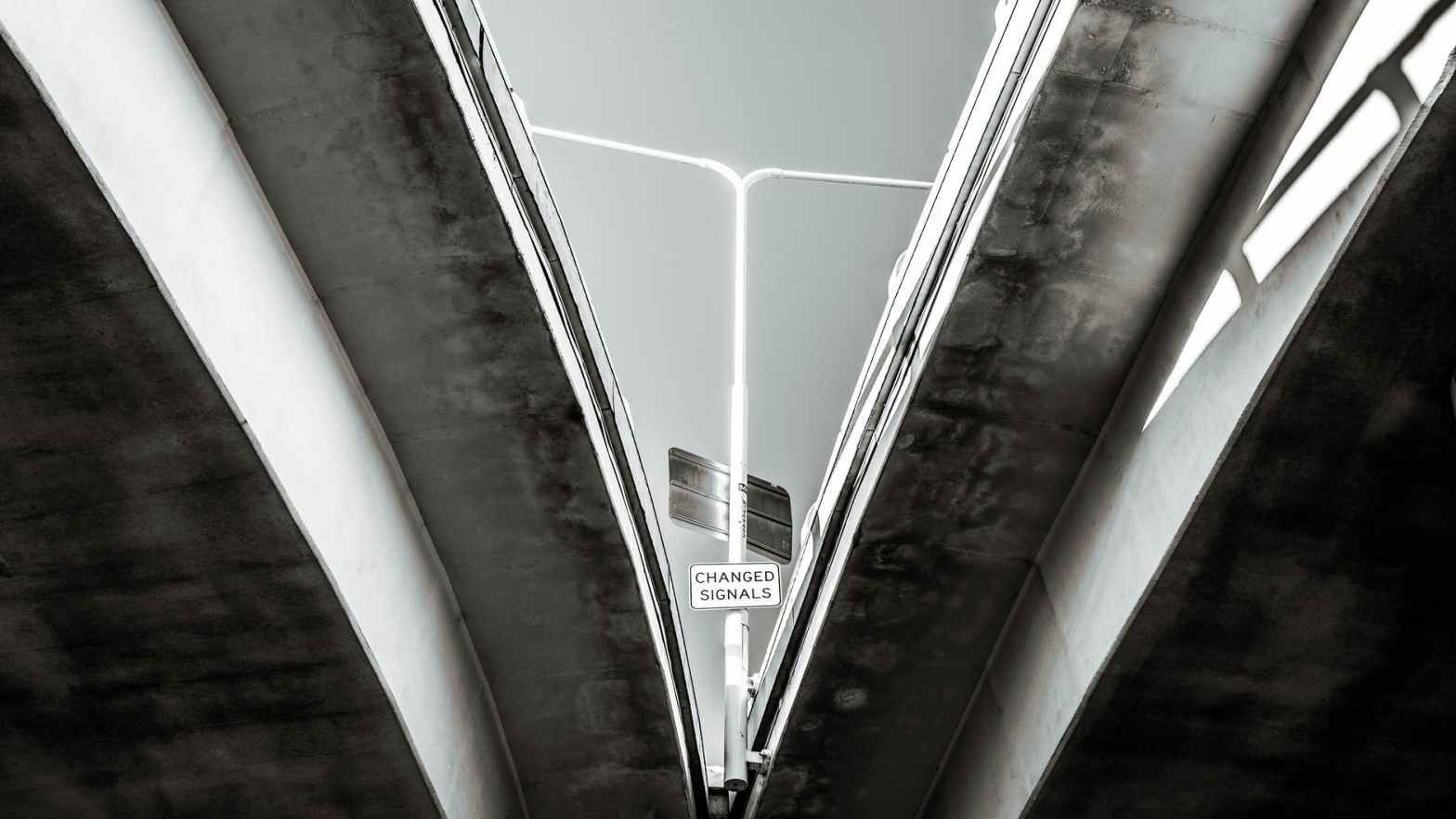

Have you ever stood on the edge of a cliff? I have.

When I was growing up, my family would often take trips to the mountains in my part of Canada. On these trips, we would sometimes go on day hikes.

As we would walk trails that were, until that time, unknown to us, we would go through forests, beside rivers, and into deep ravines. Sometimes we would walk along narrow paths with steep inclines on one side and sheer dropoffs on the other. While on these paths, the sound of rushing water would often burble up from somewhere far below us.

When making our way carefully along these paths, I would typically get a peculiar feeling in my stomach. On the one hand I was impressed by the sheer immensity of the scenery around me. On the other hand, I knew that if I was careless or lost my footing, I would plunge off the path into whatever lay beneath. Somehow, my body knew better than my mind that danger was nearby–so I better pay attention.

My body knew better than my mind that danger was nearby–so I better pay attention.

While it has been many years since I was last in the mountains, that peculiar feeling sometimes returns to my body. Typically it comes when I am facing a big decision about my future. I may not be in danger of plunging off a narrow path in the Rocky Mountains. But on my life’s path, in such moments my body suggests I am in danger of emotional or spiritual injury.

Now, some have suggested such feelings ought to be ignored. Making decisions, they say, is a purely rational process of weighing the pros and cons of whatever choice we are making.

Others argue we should envision the worst possible outcomes of our decision. Once we’ve done that, the various options in front of us will become clear. It’s unlikely the worst will happen. But, if it does, we can now choose the least worst from several terrible options.

Now, both these approaches can relieve whatever dreadful feelings might surface when approaching life’s turning points. But we can also navigate decisions in ways that are both emotionally and spiritually fulfilling.

When taking a first step in this direction, then, we might recall the path that brought us to the point of decision. Everything in the past has brought us to this point: all the things over which we had no control; all the things over which we had some control. We would not be here had our lives taken a different path. And, of course, all this includes the many specific decisions we made to get us here.

For all our specific decisions: we need to take responsibility. For all the things beyond our control: we need to let these go.

For all our specific decisions: we need to take responsibility. For all the things beyond our control: we need to let these go.

In a second step, then, we might consider the vantagepoint we now occupy. What are the values that brought us to this point? How have we embodied these values in our previous decisions? How might we have fallen short of living these values in past choices? How do we want to embody these values into the future?

For the times we embodied our values: we can be thankful. For the times we fell short of living them: we might choose to seek forgiveness.

For the times we embodied our values: we can be thankful. For the times we fell short of living them: we might choose to seek forgiveness.

In some ways, neither of these steps seems remarkable or different from anything anybody might do when making a decision rationally. But here comes the crucial piece:

As a third step we might widen our perspective to see how so many things we aren’t aware of brought us to this point. How many seemingly random conversations? How many seeming tragedies that somehow turned out alright? How many heartbreaks? How many deep and lasting joys?

But this is not the end of it. We could not have had any of these experiences if we were not connected to all other people, all other creatures, all other beings throughout physical and spiritual domains.

For example, my life in Canada is dependent on fruit growers in the Caribbean and clothing manufacturers in Asia. I am also dependent on ocean currents that moderate my weather, and cosmic radiation that affects the activity of the sun.

I need our planet to travel around our sun on its annual orbital path. This lets my earthly life flourish in accordance with its yearly seasonal cycle.

I require our solar system to maintain its position in the Milky Way. When our solar system has a consistent position in relation to other stars and planets, life on earth continues as it should. Life might not continue if other planets and stars moved to different locations.

Now, you’re probably thinking: “What’s the point of all this? Why have we gotten into all this cosmic mumbo-jumbo?!”

I’ll tell you why: When we view our lives this way, we can see how the universe itself has conspired to bring us to this point of decision. A unique balance of cosmic forces has influenced me, all my human relationships, and everything in the physical universe in ways I’ll never be able to understand.

Whatever decisions I might make will therefore have some influence on how things unfold for me. But, in reality, my influence is so small and my life so tiny, I can do little to predict or control the outcomes of any of my decisions. The forces in play are simply too great.

My influence is so small . . ., I can do little to predict or even control the outcomes of any of my decisions. The forces in play are simply too great.

So, now we are definitely on the edge of a cliff.

If I sit with how small I really am, even for a minute, I could easily sink into despair. What really is the point of anything if all I am is a speck of dust in an infinite universe?

But, in this realization, there is also a great opportunity:

What if I can consciously participate in the movements of the universe? What if I can attune myself to the deep and thrumming rhythms of the eternal cosmic dance? What if I can make myself a conduit for the consciousness that holds all of reality together?

Now, these are questions that need to inform every decision I make!

When I take these questions seriously, the bottom line is whether my choice will bring me into greater alignment with the cosmic forces, or whether it will take me out of alignment. Will my choice bring me into deeper relationship with all that is, or will it destroy that relationship, even in part?

. . . the bottom line is whether my choice will bring me into greater alignment with the cosmic forces, or whether it will take me out of alignment.

These are challenging questions, especially for those of us who live in the global West.

In the West we believe ourselves to be in complete control of our lives. We believe we are the only ones who can tell ourselves what to do. We even like to believe we can command the powers of life and death–our fondness for the accomplishments of modern western medicine is a case in point.

To discover we have limited influence over the unfolding of our lives can be very unsettling. To discover we can’t control the outcomes of our decisions can make us feel even more uncomfortable. These discoveries don’t match how we’ve come to view ourselves.

But it is healthy to shift our perspective to explore questions of alignment with the cosmos. To treat ourselves as isolated from the rest of the universe is a deeply unrealistic way of engaging life.

The result is we need to see ourselves as always standing on the edge of infinity.

All of life, all of reality, always surrounds us. All of us are simply nodal points in an infinite network of beings. Our responsibility is therefore to explore how best we can respond to the needs of those around us, keeping in rhythm with where we are in life and where we are in relation to others.

Our responsibility is . . . to explore how best we can respond to the needs of those around us, keeping in rhythm with where we are in life.

When thinking of decisions this way, we might ultimately be invited to live the following paradox: By letting go of their specific concerns, individual people can enlarge who they are; by seeing their connection to all of reality, individual lives can take on cosmic significance.

So, while we may feel we’re on the edge of a cliff when confronted with a big choice, in reality we’re standing on the edge of infinity. When we choose, intentionally, to let infinity inform our decision, and, when we choose to let infinity live more fully in us, that’s when we’ve also chosen to uphold our spiritual integrity.

_________________________

Any decision has immense implications. But so could be the impact of everyone’s life if such immensity is taken seriously.

Disclaimer: The advice and suggestions offered on this site are not substitutes for consultation with qualified mental or spiritual health professionals. The perspectives offered here are those of the author, not of those professionals with whom readers might have relationships as clients or patients. In crisis situations, readers are encouraged to contact these professionals for appropriate support and treatment if needed.